Unit 1: Atomic Structure

Energy is Quantized!

- Formula: E = hf = hc/λ

- Wavelength and energy relationships:

- UV > Vl > IR (in terms of energy and frequency)

- Wavelength increases in the order: UV < Vl < IR

Photoelectric Effect

- Light photons of specific wavelengths or frequencies are used to excite or eject electrons.

- Formula: Energy of photons = B.E (Binding Energy) + K.E (Kinetic Energy).

Coulombic Force

- Coulomb’s Law: q₁q₂ / r

- Ionic, metallic, Lattice, Hydration

Electron Configuration

- 1s 2s 2p 3s 3p 4s 3d

- Cr , Cu exception

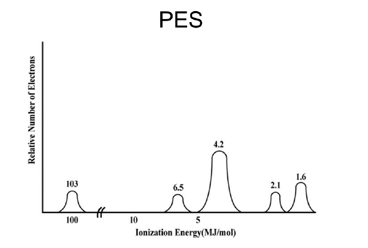

Photoelectron Spectroscopy (PES)

- Intensity (y-axis) corresponds to the number of electrons.

- Binding energy (x-axis) represents electron removal energy.

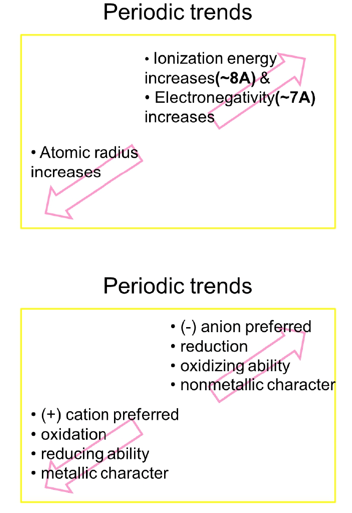

Periodic Trends

Proton no = Nuclear charge

Shell no = Energy level = Shielding no

Ions – HO¹⁻, NH₄¹⁺, NO₃¹⁻ , CO₃²⁻ , SO₄²⁻ , PO₄³⁻

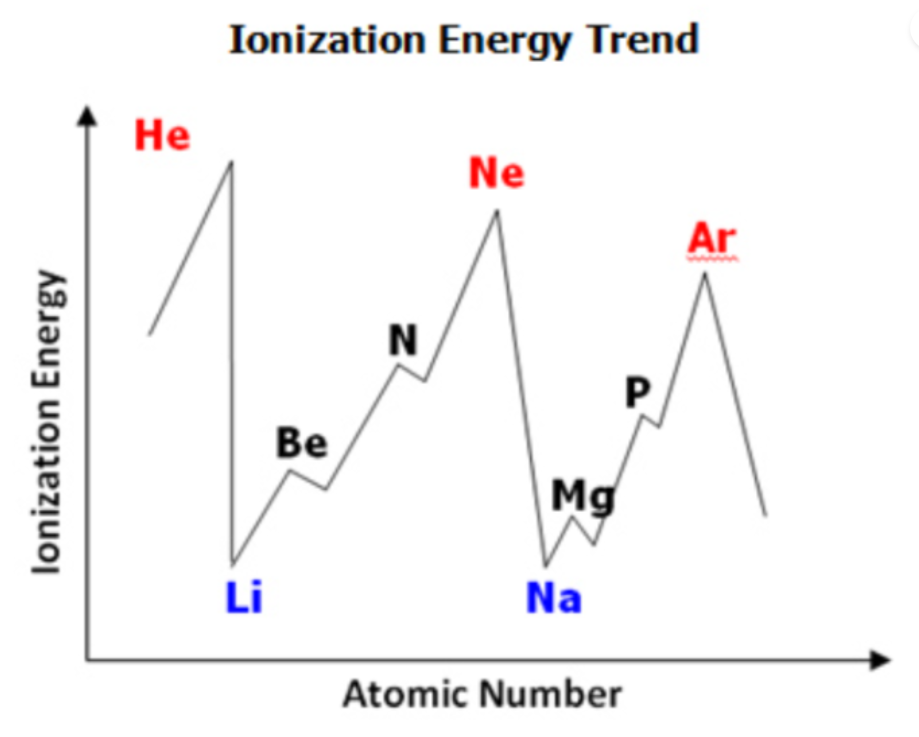

Ionization energy Excemption

- Ionization energy values decrease:

- From Be to B (due to p orbital initiation).

- From N to O (due to paired electrons in p orbital).

- Electron Affinity ( Exothermic)

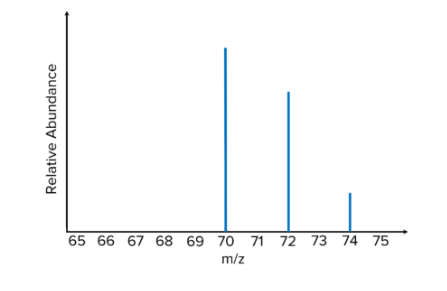

Mass Spectrometer

- Calculates average atomic mass.

- Example: Bromine isotopes

- ⁷⁹Br (50.5%)

- ⁸¹Br (49.5%)

Unit 2: Chemical Bonding

Metallic Bond

- Free electrons = delocalized electrons = valence electrons.

- Examples: Li < Mg (bond strength – Coloumb law)

- Metal related to Ionization Energy , Nonmetal related to Electron Affinity

- Malleability and Ductility

- Types:

- Interstitial Alloy: Different radii, more rigid.

- Substitutional Alloy: Comparable radii, malleable, ductile.

Ionic Bond

- Transferring electron(s)

- Bond strength proportional to Coulomb’s law.

- Examples: LiF > NaCl , LiF < MgO.

- Lattice Energy:

- Formula: XY(s) → X⁺(g) + Y⁻(g).

- lattice stucture

Covalent Bond

- Sharing electrons.

- Types:

- Network Covalent Solids: Ex) C (diamond, graphite), SiO₂ , Si

- Molecular Substances: Ex) H₂O, CO₂, N₂.

- allotrope vs isotope vs isomer

- Strength – Intermolecular Forces

| Solid Type | Metallic Solids | Ionic Solids | Molecular Solids |

|---|---|---|---|

| Properties | – Good conductors | – Do not conduct, but conduct when melted/ dissolved in water | – Do not conduct – Acid , Base and graphite exception |

| Malleable/ductile | Low vapor pressure | – Low melting point (Except to Giant covalent) | |

| – Brittle | – Composed of discrete molecules | ||

| Group 1, NO₃⁻ , NH₄⁺ Absolutely Dissolve | – “Like dissolves like” principle applies |

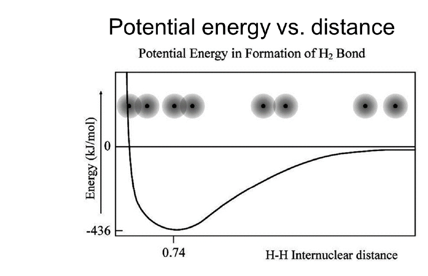

Covalent Bonds and Potential Energy

Lewis Struture

CH₄, CH₂=CH₂, NH₃ , NH₄⁺ , CH₃COOH, CH₃COO ⁻ , CH₃COOCH₃, CO₃²⁻ , SO₄²⁻ , PO₄³⁻

from period 3, octet expanded

Bond Energy

- Energy required to dissociate a bond in a gaseous state.

- Endothermic , (Bond Formation – Exothermic)

Bond Length

- Distance between nuclei where potential energy is minimized.

Polar vs. Nonpolar Bonds

- Bond : Electronegativity difference

- Molecular Polar – Asymmetric arrangement, Bond polarities not Cancel out, dipole Moments.

Resonance

- Not dynamic equilibrium

- Equivalent bond length and strength

- Only their average form exists (Bond order / # Resonance)

- Delocalized pi electrons.

- Enhance The Stability

- C₆H₆ , NO₃¹⁻ , CO₃²⁻ , SO₄²⁻ , PO₄³⁻ examples

Formal Charge

- Formal charge = original v.e – (# Lone e + # Bond )

- Zeros are preferred!

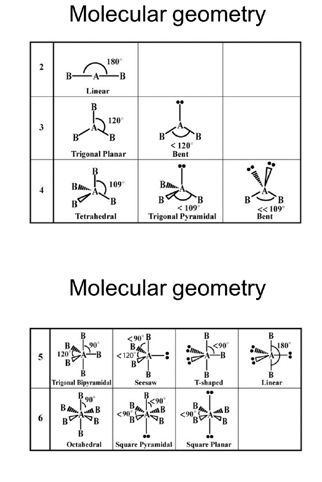

VSEPR Theory

- Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion.

- Minimizes repulsion:

- Bonding pair–bonding pair < bonding pair–lone pair < lone pair–lone pair.

- Molecular geometry vs Electron domain geometry

Hybridization

- Types: sp, sp², sp³.

Unit 3: IMF and Gas

Intermolecular Forces

- Strength – Intermolecular Forces determine melting and boiling points, Vapour pressure and Volatility. (Physical state)

London Dispersion Forces (LDF)

- Instantaneous dipoles, Temporary Foreces, Induced Dipoles.

- Present between all molecules, especially nonpolar.

- Increased by:

- Larger # electrons.

- Larger electron clouds.

- Greater polarizability.

Dipole-Dipole Interaction

- Present between polar molecules.

- Stronger than LDF but weaker than hydrogen bonding.

- Permanent Forces

Hydrogen Bonding

- Strongest intermolecular force.

- Examples: H bonded to F, O, or N.

Dipole-Induced Dipole Force

- Present between polar and nonpolar molecules.

- Stronger than LDF but weaker than dipole-dipole forces.

Ideal Gas Law and Partial Pressure

- Formula: PV = nRT

- Partial Pressure : Total pressure x mole Fraction

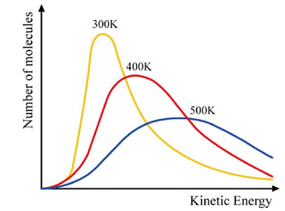

Kinetic Molecular Theory

- Ideal gas behavior

- Random & constant motion

- Perfectly elastic collision

- No intermolecular forces

- Negligible volume of particles (point-like)

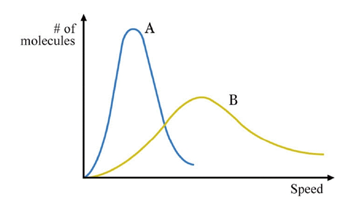

Kinetic Energy vs. Speed

- Although AVERAGE kinetic energy values are always constant for all gases

- Speed = v∝√(T/Mr)

Ideal Gas vs. Real Gas

- Ideal Gas

- Higher T, Lower P, Volum negligible, No Attraction

- Condition for less ideal:

- High P ➔ The combined volume of the particles becomes significant.

- Low T ➔ The intermolecular forces become significant due to their slow motion.

Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution

Unit 4. Stoichiometry

Some Formulas

- Percent Yield: (actual yield / theoretical yield) × 100

- Percent Error: |theoretical − actual| / theoretical × 100

- Average Atomic Mass: Σ(mass of each isotope × % abundance)

Solubility Rule

- Every group 1A elements, NH₄⁺, NO₃⁻ containing salts are always soluble without exception.

- Strong Acid – H ⁺ , OH ⁻

Balancing Redox Reactions

- Balance element except O, H

- Balance O using H₂O

- Balance H using H⁺

- Balance charge using e⁻

Unit 5: Kinetics

Reaction Rate

- Definition: The slope of the graph of concentration vs. time.

- Change in concentration over time.

- Unit: M/s or mol/L·s.

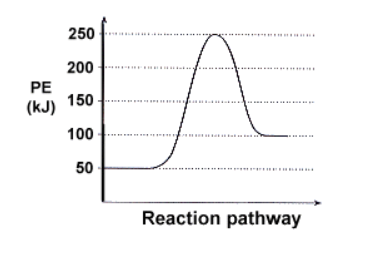

Collision Theory

- Must Collide

- Proper Orientation

- Sufficient Energy greater than activation energy.→ Leads to effective collision (enables the reaction to occur).

Factors Affecting Reaction Rates

- Surface Area ( Smaller Size ) : Frequencies of Collision

- Concentration. – Frequencies of Collision

- Pressure and Volume. – Frequencies of Collision

- Temperature. 1) Velocity – Frequencies of Collision , More particles have Higher KE than Activation Energy

- Catalyst. – Lower Activation Energy → More particles have Higher Kinetic Energy than Activation Energy

Rate Law

- General Form: mA + nB → product

Rate = k × [A]ᵐ × [B]ⁿ - Reaction orders (m, n) are determined by experiment only.

- The unit of rate constant, k, depends on the overall reaction order.

- Rate constant is affected by temperature and the presence of a catalyst.

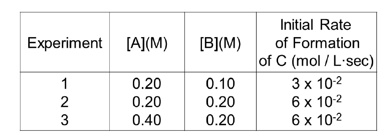

Rate Law Determination

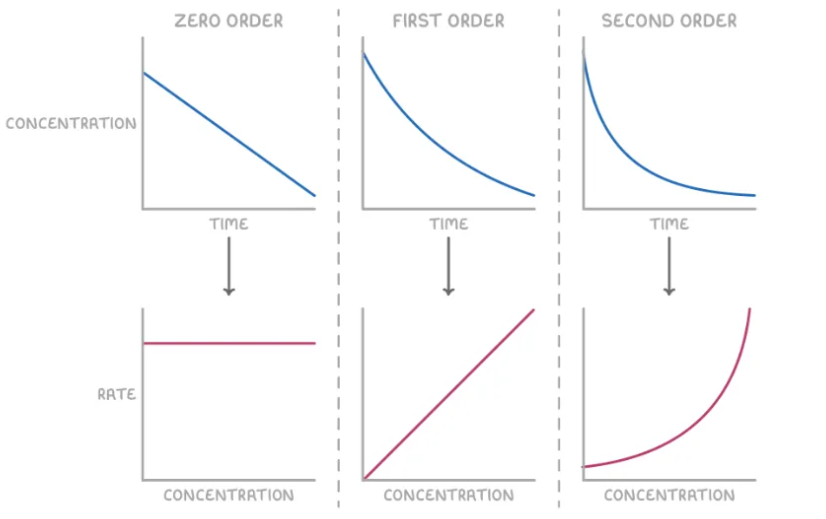

Experimental rate law (concentration vs. rate).

Rate law Diagram

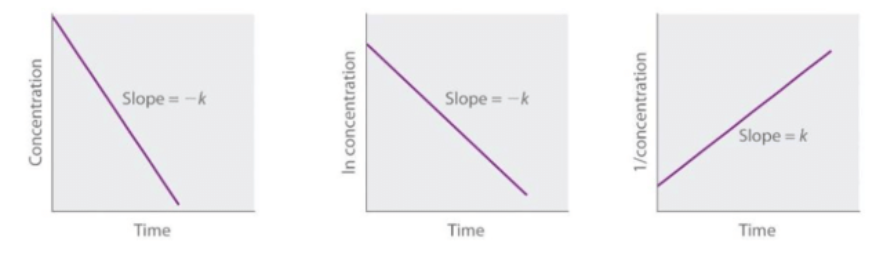

Integrated rate law (concentration vs. time).

- Zero Order: [A] = -kt + [A]₀

- First Order: ln[A] = -kt + ln[A]₀ (Half-life = 0.693/k).

- Second Order: 1/[A] = kt + 1/[A]₀

Reaction mechanism.

- A multistep reaction occurs as follows:

2A + B ⇌ C (fast, reversible) C + E → D + A (slow). - Overall Reaction Equation: A + B + E → D

Intermediate: **C** Catalyst: **A** - Rate Law:Rate = k[A]²[B].

Unit 6: Thermodynamics

Key Topics:

- Exothermic vs. Endothermic Reactions

- Standard Enthalpy Change (ΔH°) Calculations:

- Using calorimetric data: ΔH° = -q / mol , q = mct

- Hess’s Law: Sum of enthalpy changes of individual reactions

- Using bond energies, Combustaion energies: ΔH° = ΣB.E(reactants) – ΣB.E(products)

- Using formation energies

**ΔH° = Σproducts - ΣReactnats**

Entropy change (ΔS) Calculations

- Distribution higher → entropy change increases

- Calculation :

**ΔH° = Σproducts - ΣReactnats**

Spontaneity of Reactions

- ΔH°: Exothermic reactions (ΔH° < 0) are preferred.

- ΔS°: Higher entropy (ΔS° > 0) is preferred.

- ΔG°: Determines spontaneity (ΔG° = ΔH° – TΔS°).

Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG°):

- If ΔG° < 0: Reaction is thermodynamically favored. ΔG° = ΔH° – TΔS° ΔG° = -RT lnK ΔG° = -nFE°

- Temperature-dependent spontaneity:

- High T: ΔS-driven.

- Low T: ΔH-driven.

Unit 7: Equilibrium

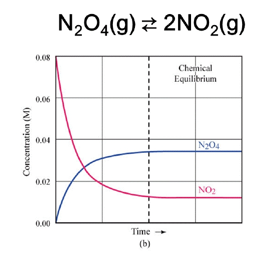

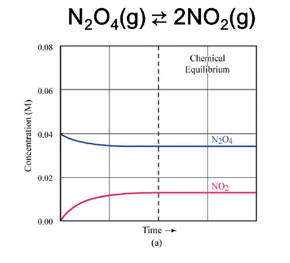

- Meaning of Equilibrium

- Concentrations Constant

- Forward and reverse reaction rates are equal.

- Reversible vs. Irreversible Reactions

- Irreversible reactions (e.g., combustion, precipitation and gas produced)

- Expression:

Kₑq = [C]ᶜ[D]ᵈ / [A]ᵃ[B]ᵇ- Includes only gases and aqueous phases.

Factors Affecting Equilibrium

- Temperature:The only factor that changes Keq.

Relationship Between Keq and Q

- Q > Keq: Shifts left (toward reactants).

- Q < Keq: Shifts right (toward products).

- Q = Keq: The system is at equilibrium.

Le Chatelier’s Principle

- Types of Stress:

- Concentration Changes: Adjusts to restore equilibrium.

- Pressure Changes (via Volume):Affects gases; shifts to favor fewer or more moles of gas.

- Temperature Changes:Alters Keq (forward reaction is endothermic or exothermic reactions).

- Catalysts:Speed up the both reactions equally but do not affect Keq.

- Examples:

- N₂(g) + 3H₂(g) ⇌ 2NH₃(g) ΔH < 0

Manipulation of Equilibrium – rule

Ksp

- Definition of Ksp

- Soluble salt: AB₍aq₎ → A⁺₍aq₎ + B⁻₍aq₎ (Completely dissociated)

- Insoluble salt: AB₍ₛ₎ ⇌ A⁺₍aq₎ + B⁻₍aq₎ / Kₛₚ = [A⁺][B⁻]

- Basic Calculation

- If molar solubility = x:

- Kₛₚ of AB compound = x²

- Kₛₚ of AB₂ compound = 4x³

- If molar solubility = x:

- Common Ion Effect

Unit 8 : Acids and Bases

Common Acids and Bases

- Strong Acids: HCl, HBr, HI, H₂SO₄, HNO₃, HClO₄,

- Strong Bases: NaOH, KOH, Group 1A, 2A hydroxides.

- Weak Bases: NH₃, Fe(OH)₂, Al(OH)₃, Transition metal + OH

pH Calculation Formulas

- Strong Acids and Bases

pH (Strong Acid)=−log[H+] pOH (Strong Base)=−log[OH−]pH + pOH = 14 - Weak Acids pH = -log√(Ka × C)

pOH = -log√(Kb × C)

Percent Dissociation

%Dissociation=√(Ka/C) × 100

Acids and Bases with Water

- HCl + H₂O → H₃O⁺ + Cl⁻

- Cl⁻ + H₂O → HCl + OH⁻

- HF + H₂O ⇌ H₃O⁺ + F⁻

- F⁻ + H₂O ⇌ HF + OH⁻

Neutralization (Acid + Base , Carbonate and Metal)

- HCl + NaOH → H₂O + NaCl

- H⁺ + OH⁻ → H₂O

- HF + NaOH → H₂O + NaF

- HF + OH⁻ → H₂O + F⁻

- HCl + Na₂CO₃ → H₂O + CO₂ + 2NaCl

Ionic Equation: 2H⁺ + CO₃²⁻ → H₂O + CO₂ - HCl + Zn → ZnCl₂ + H₂

Ionic Equation: 2H⁺ + Zn → Zn²⁺ + H₂

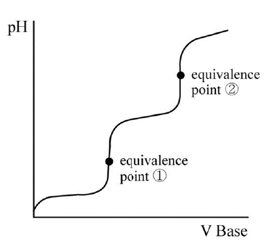

Dissociation of a Polyprotic Acid

- H₂CO₃ + H₂O ⇌ H₃O⁺ + HCO₃⁻ Kₐ₁

- HCO₃⁻ + H₂O ⇌ H₃O⁺ + CO₃²⁻ Kₐ₂

Key Point:

- Kₐ₁ >> Kₐ₂

Neutralization of a Polyprotic Acid

- H₂CO₃ + 2NaOH → 2H₂O + Na₂CO₃

- Step 1: H₂CO₃ + NaOH → H₂O + NaHCO₃

- Step 2: NaHCO₃ + NaOH → H₂O + Na₂CO₃

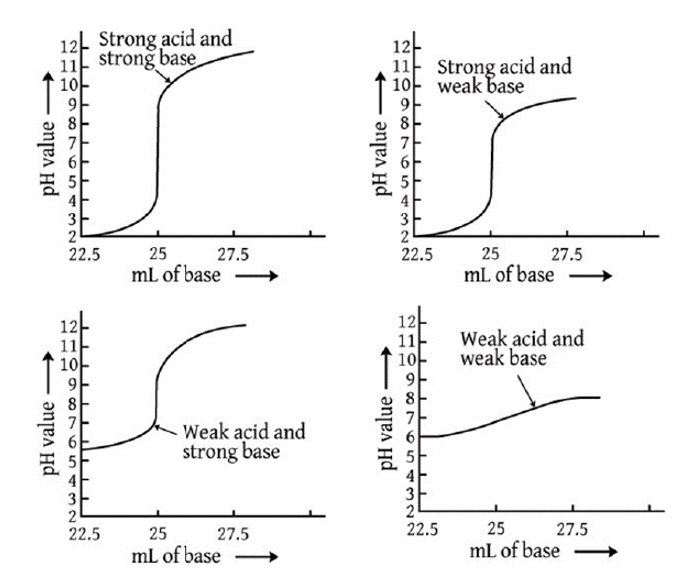

pH at the equivalence point

- Strong acid + strong base → neutral salt Example: HCl + NaOH → NaCl + H₂O / H⁺ + OH⁻ ⇌ H₂O

- Strong acid + weak base → acidic salt Example: HCl + NH₃ → NH₄Cl / H⁺ + NH₃ → NH₄⁺

- Weak acid + strong base → basic salt Example: HC₂H₃O₂ + NaOH → NaC₂H₃O₂ + H₂O HC₂H₃O₂ + OH⁻ → C₂H₃O₂⁻ + H₂O

- Weak acid + weak base → X

- CV = CV (Volume and Concentration)

- Whether acid is strong or weak, the volume of base is identical

Hydrolysis of Salt

Why NH₄Cl is acidic

- Cl⁻ ion cannot react with water molecules, but NH₄⁺ does to a small extent.Example:

- NH₄⁺ + H₂O ⇌ NH₃ + H₃O⁺

Why NaCl is neutral

- Na⁺, Cl⁻ ions cannot react with water molecules.

Why NaC₂H₃O₂ is basic

- Na⁺ ion cannot react with water molecules, but C₂H₃O₂⁻ does to a small extent.Example:

- C₂H₃O₂⁻ + H₂O ⇌ HC₂H₃O₂ + OH⁻

How to prepare a buffer

Composition (by 1:1)

- Weak acid + conjugate base HF + NaF / HC₂H₃O₂+NaC₂H₃O₂

- Weak base + conjugate acid NH₃ + NH₄Cl

Composition (by 2:1)

- Weak acid + strong base HF + NaOH / HC₂H₃O₂ + NaOH

- Weak base + strong acid NH₃ + HCl

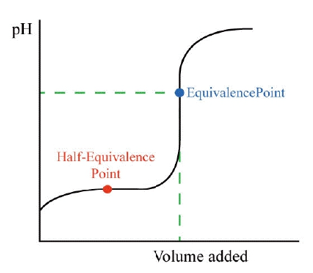

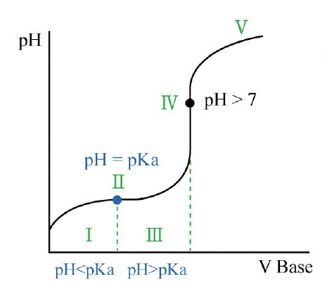

Half-equivalence point

- Best buffer ratio!

- pH = pKa

Handerson-Hasselbalch equation

- pH = pKa + log [A⁻]/[HA]

- Used for only a buffered solution.

Choosing a good indicator

- pKa of the indicator needs to be close to the pH at the equivalence point.

- Lechatelier’s priciple

| Indicator | pKa | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Methyl Red | 5.5 | S.A. + W.B. |

| Bromothymol Blue | 7.1 | S.A. + S.B. |

| Phenolphthalein | 8.7 | W.A. + S.B. |

W.A. and S.B. (buffering region)

- pH < pKa: [HC₂H₃O₂] > [C₂H₃O₂⁻ ]

- pH = pKa:

[HC₂H₃O₂] = [C₂H₃O₂⁻ ] - pH > pKa:

[HC₂H₃O₂] < [C₂H₃O₂⁻ ] - higher Ka , higher Dissociation(Ionization)

Unit 9 : Cell and Others

Reaction:

- Cu² ⁺ + 2e⁻ → Cu , E° (Reduction Potential) =+0.34V

- Zn² ⁺ + 2e⁻ → Zn , E° (Reduction Potential) =−0.76V

Zn + Cu² ⁺ → Zn²⁺ + Cu, E° cell (Cell Potential) = 1.10 V

How Ecell changes with concentrations:

- Cell #1:

- [Cu²⁺] = 1.0 M, [Zn²⁺] = 1.0 M

- E° cell = 1.10 V

- Cell #2:

- [Cu²⁺] = 0.1 M, [Zn²⁺] = 1.0 M

- Ecell < 1.10 V

- Cell #3:

- [Cu²⁺] = 1.0 M, [Zn²⁺] = 0.1 M

- Ecell > 1.10 V

- Cell #4:

- [Cu²⁺] = 0.1 M, [Zn²⁺] = 0.1 M

- E° cell = 1.10 V, but it runs for a shorter time.

Equilibrium and Dead Battery

- Q = 1: E° cell = Ecell

- Q > 1:

- More Products (P), Less Reactants (R)

- Ecell < E° cell

- Closer to equilibrium

- Q < 1:

- Less Products (P), More Reactants (R)

- Ecell > E° cell

- Farther from equilibrium

Electrolysis

Electrolysis of molten salt:

- Reaction: 2NaCl → 2Na + Cl₂

- Na⁺ + e⁻ → Na (E° = -2.71 V)

- Cl₂ + 2e⁻ → 2Cl⁻ (E° = 1.36 V)

- Overall cell potential: E° cell = -4.07 V

- External electrical current > 4.07 V is needed.

- Electrolysis is non-spontaneous and requires energy.

Reactivity Comparison

- Order of reactivity for metals X, Y, Z:

- If X doesn’t react with Y(NO₃)₂ but reacts with Z(NO₃)₂:

- Reactivity: X < Z < Y (The highest Reducing agent)

- Tendency to lose electrons determines reactivity.

- If X doesn’t react with Y(NO₃)₂ but reacts with Z(NO₃)₂:

Metal Deposition

- Equation : q = It = nF

- How many grams of Al can be deposited from Al(NO₃)₃ solution by 2.0 A for 10 minutes?

- Answer: 0.11 g

- How long does it take to deposit 10.0 g of Cu from Cu(NO₃)₂ solution by 5.0 A?

- Answer: 6100 seconds or 1.0 x 10² minutes

- How many grams of Al can be deposited from Al(NO₃)₃ solution by 2.0 A for 10 minutes?

Laboratory

Solution Preparation (1): How to prepare 100 mL of 1.00 M NaCl solution

- Measure 5.85 g of NaCl using an electronic balance.

- Add the NaCl to a 100 mL volumetric flask.

- Add a small amount of water and swirl to dissolve completely.

- Fill the flask with water until the meniscus reaches the 100 mL mark.

Solution Preparation (2): How to prepare 500 mL of 0.10 M H₂SO₄ solution

- Wear safety goggles and gloves.

- Use M₁V₁ = M₂V₂ to calculate the volume of concentrated H₂SO₄ needed (25 mL).

- Add water to a volumetric flask first.

- Carefully add the acid to the flask.

- Add more water until the total volume reaches 500 mL.

Beer’s Law

- A = abc

- A: Absorbance (no unit)

- a: Absorptivity constant (M⁻¹cm⁻¹)

- b: Path length (cm)

- c: Concentration (M)

- Graph: Absorbance vs. Concentration

- Chromatography As solvent rises onto the paper, solute A~D reaches specific points depending on their intermolecular forces with the solvent molecules. In order of increasing interaction with the solvent: A < B < C < D

- Physical Separation Methods

- Filtration: Insoluble solid from liquid

- Distillation: Soluble solid from liquid or miscible liquids using boiling point differences

Lab Safety

- Never pour water to acid, as it might cause vigorous splattering due to rapid heat increase.

- Pour acid to water slowly to ensure proper absorption of heat.

- Never return residue of chemicals to the reagent container.

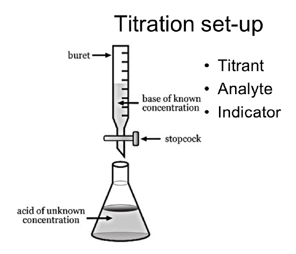

Titration

- Be careful with the buret:

- Rinse it with titrant twice before use. – water , titrant

- Choose an indicator with a pKa close to the equivalence point pH.

Gravimetric Analysis

- Example: A student determines the mass % of silver in a copper-silver alloy.

- Add saturated NaCl(aq) until no more precipitate forms.

- Filter, wash, dry, and weigh the precipitate.

- Repeat until a constant mass is achieved.

Dehydration of Hydrated Salt

- Cover the crucible to avoid mass loss.

- Measure repeatedly to ensure complete dehydration.

Gas Collecting via Water Displacement

- Adjust the graduated cylinder to equalize water levels.

- Consider vapor pressure, determined by temperature.

Significant Figures

- Examples:

- 0.010 g

- 100. mL

- log 0.010 = 2.00

- Rules:

- Addition/Subtraction: Use the fewest decimal places.

- Multiplication/Division: Use the fewest significant figures.